Why are imported goods comparatively more expensive in Bangladesh?

Why are imported goods comparatively more expensive in Bangladesh?

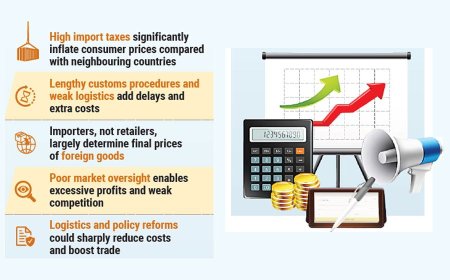

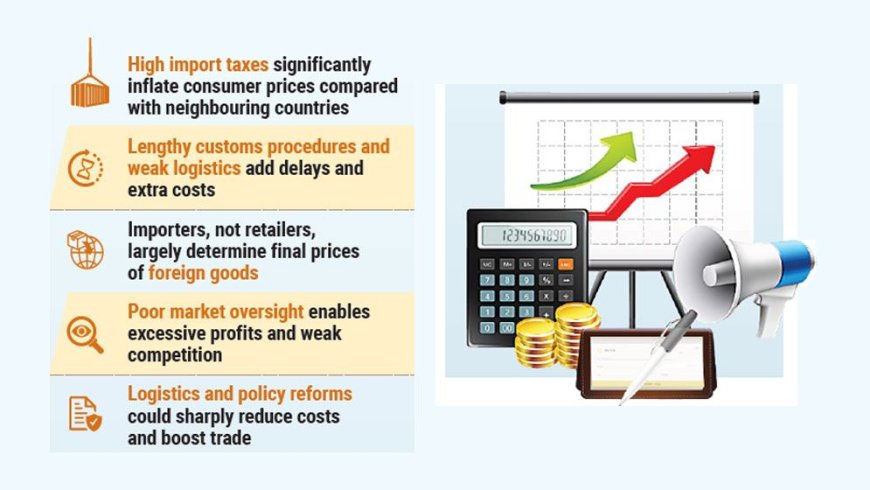

Bangladesh relies heavily on imports—ranging from industrial machinery to everyday consumer items—yet many of these products reach local markets at prices significantly higher than in neighbouring countries such as India. This price gap is placing increasing pressure on household budgets and prompting questions about inefficiencies in the country’s import system.

The issue is gaining urgency as Bangladesh is projected to become the world’s ninth-largest consumer market by 2030, a shift that will likely deepen import dependence. Economists and business leaders warn that without structural reforms, the cost of imported goods will continue to climb, with adverse effects on consumers and the broader economy.

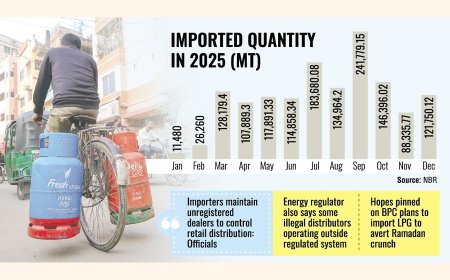

According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), the country imported goods and services worth approximately $95.3 billion in the 2024–25 fiscal year (FY25). Of this, goods accounted for $84.83 billion and services $11.6 billion. Exports during the same period totalled $54.83 billion—$48.28 billion in goods and $6.55 billion in services. In the previous fiscal year, imports stood at $86.72 billion, while exports amounted to $58.03 billion.

A comparison of retail prices highlights stark disparities between Bangladesh and India for common imported products. In Dhaka supermarkets, a 500-gram packet of California almonds sells for $8–8.5, compared with $5.46–6 in India. A 462-gram jar of Skippy peanut butter costs $7–7.5 in Bangladesh but $4.48–5 in India. Heinz tomato ketchup (570g) is priced at around $6 in Dhaka, versus $4.49 in India, while Gerber baby cereal (227g) sells for $10.5–13 in Bangladesh—nearly double India’s price of $5.64.

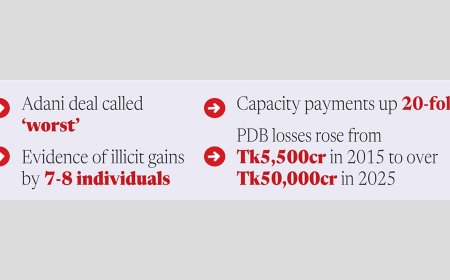

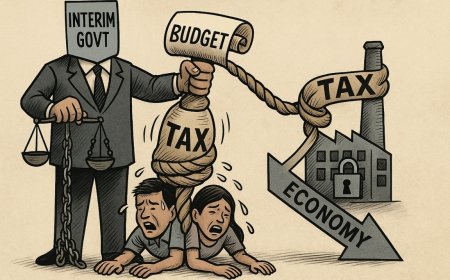

Data from the National Board of Revenue (NBR) indicate that high import taxes are a major contributor. California almonds imported at $4 face a combined tax burden of 61.8%. Skippy peanut butter, imported at $4.25, attracts taxes of 88.75%. Heinz tomato ketchup, with an import value of $1.71, is taxed at 93.16%, while Gerber baby cereal imported at $7 is subject to duties of up to 61.8%.

In contrast, India imposes considerably lower taxes: about 39.65% on almonds, 39–45% on peanut butter, roughly 39–40% on tomato ketchup, and just over 40% on baby cereal, according to Indian export-import agencies.

Delays in clearance further inflate costs. Industry insiders say it takes an average of 9.57 days to release imported milk powder in Bangladesh, including physical inspections and testing, compared with just 3.6 days in India.

Complex procedures and weak logistics

Business leaders cite cumbersome documentation and port inefficiencies as key drivers of higher prices. Mohammad Borhan E-Sultan, president of the Bangladesh Foodstuff Importers and Suppliers Association (BAFISA), said importers must navigate at least 13 separate stages before goods are released, involving banks, shipping agents, customs officials, testing bodies and port authorities.

“This lengthy and complex process disrupts business operations and causes significant delays in both import and export activities,” he said, adding that incoherent policies, inefficient logistics, prolonged customs procedures and limited technological adoption at ports all raise the cost of doing business.

Who determines prices?

Imported goods are largely sold through supermarkets, but retailers say pricing is beyond their control. Zakir Hossain, general secretary of the Bangladesh Supermarket Owners’ Association (BSOA), said importers set prices after factoring in taxes, costs and profit margins.

“Supermarket margins are limited due to competition,” he said, rejecting allegations of syndication among retailers.

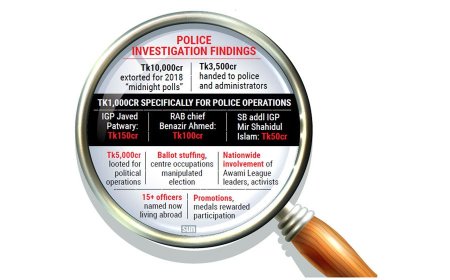

Governance and oversight concerns

Consumers and advocacy groups argue that weak governance exacerbates the problem. Rezaul Karim, a corporate professional who has travelled extensively across Asia, Europe and the United States, said everything from baby food to luxury items is far more expensive in Bangladesh.

“Traders take higher profits on foreign products due to weak market monitoring,” he said, noting that a saree priced at Tk5,000–7,000 in India or Thailand can sell for Tk15,000–16,000 in Bangladesh.

The Consumers Association of Bangladesh (CAB) echoed these concerns. Its president, AHM Shofiquzzaman, blamed higher prices on irregularities, corruption, poor logistics and weak oversight by regulatory bodies, including the Bangladesh Competition Commission (BCC), Directorate of National Consumer Rights Protection (DNCRP), NBR and Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI).

He alleged that some importers are compelled to make unofficial payments to secure document clearance, warning that prolonged lead times sharply increase costs. He also cautioned against “invisible syndication” and weak competition, noting that although profit margins on agricultural products are legally capped at 25–30%, retail prices often exceed these limits with little monitoring.

While the commerce ministry has the authority to fix prices of 24 essential commodities, he said it currently intervenes mainly in edible oil and sugar. He called for stronger political commitment, lower import duties, improved governance across supply chains and more reasonable profit margins.

Supply-chain pressures

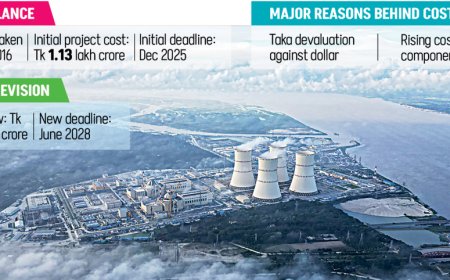

BAFISA’s Borhan E-Sultan also pointed to broader supply-chain challenges. A depreciating taka and higher dollar exchange rates increase import costs, while rising freight, insurance and shipping charges are passed on to consumers.

He noted that imported food items face additional costs from customs duties, regulatory fees and compliance requirements such as food-safety testing and certification. Long clearance times, port and shipping demurrage, weak cold-chain infrastructure and multiple intermediaries further push up retail prices.

Calls for reform

Importers argue that reducing duties could lower prices while increasing consumption and tax revenue. Borhan said lower tariffs would encourage formal imports and reduce under-invoicing and smuggling. He also recommended simplifying certification requirements, allowing a second test if products fail initial inspections, and prioritising clearance within three days to reduce demurrage and stabilise prices.

Logistics and competitiveness

Economists stress that improving logistics could significantly enhance competitiveness. Dr M Masrur Reaz, chairman of Policy Exchange of Bangladesh, said trade facilitation is now a critical driver of economic performance.

Bangladesh ranked 88th out of 139 countries in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index 2023, far behind India (38th) and Vietnam (43rd). Reaz said a 25% reduction in logistics costs could boost exports by 20%, while a 1% cut in transport costs could raise exports by 7.4%. Reducing dwell time by just one day could yield similar gains.

“If there were no congestion, truck operators’ total costs would fall by 35.5% on average,” he said, adding that in-transit inventory carrying costs could decline by as much as 84%. He urged the adoption of automated, technology-driven logistics systems and full automation of customs and clearance processes.

Official response

The Bangladesh Competition Commission says it is working to strengthen its capacity. Its secretary, Mahbubur Rahman Khan, said additional staff would be recruited to improve market monitoring and that complaints over abnormal pricing would be investigated.

Meanwhile, Commerce Adviser Sk Bashir Uddin said a draft Import Policy Order for 2025–2028 has been prepared and is awaiting cabinet approval. He said the ministry is pursuing “structural, procedural and cultural changes” to simplify trade operations.

What's Your Reaction?