Plenty in the fields, pricey in the markets: Why are vegetables so expensive in Dhaka?

Plenty in the fields, pricey in the markets: Why are vegetables so expensive in Dhaka?

Winter has delivered a bumper vegetable harvest nationwide, aided by smooth transportation and ample supply. Yet consumers in Dhaka are finding little relief, as prices in city markets remain stubbornly high.

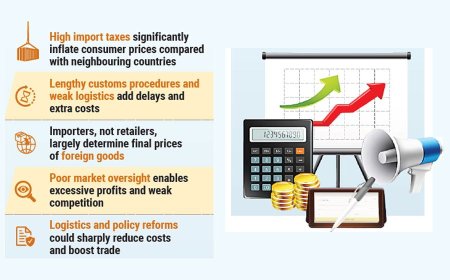

Visits to several kitchen markets show that vegetable prices have barely eased, even as farmers complain they are struggling to recover production costs. The disconnect has revived concerns about market manipulation and the outsized role of middlemen. Although Dhaka’s markets are flooded with winter produce—traditionally the cheapest season of the year—prices show little sign of softening.

Consumers continue to pay inflated rates, while farmers in producing regions say they are selling vegetables at throwaway prices. The widening gap between farm-gate and retail prices appears to be driven largely by intermediaries.

Dhaka’s wholesale markets receive winter vegetables from Bogura, Naogaon, Chuadanga, Sirajganj, Rajshahi, Jashore and other districts. Traders say more than 50 truckloads arrive daily from Bogura alone during the peak season.

Wholesalers at Karwan Bazar said supply is higher than last year, yet prices remain elevated. By late January, wholesale prices were on average Tk 20 per kg higher than a year earlier.

“Last year at this time, cauliflower sold at Tk 15–20 per kg wholesale. This year it’s Tk 30–35,” said Latif Munshi, a trader at Karwan Bazar. “We are buying at higher prices from upstream traders, so we have no choice but to sell at higher rates to retailers.”

Anwar Mia, a trader at Swarighat wholesale market, echoed the concern. “Cabbage, tomato, cucumber, carrot, bottle gourd—almost all winter vegetables—are pricier than last year. There’s no supply shortage, but intermediary costs have gone up.”

The situation is markedly different at the production level.

In Bogura’s Sherpur upazila, vegetable grower and trader Naim Meyajan said he cultivated cauliflower on nearly 10 bighas of land. While early varieties fetched good prices between September and November, prices collapsed once peak harvesting began in December.

“Wholesalers bought fields early at Tk 80,000 to Tk 100,000 per bigha, against production costs of around Tk 50,000. But once the main harvest started, buyers disappeared. I had to sell cauliflowers at Tk 5 per kg,” he said.

Farmers at Fulbari and Mohasthan haats in Bogura reported sharp price declines from late December. Many were forced to sell produce using an inflated ‘maund’ of 60 kg instead of the standard 40 kg, yet still failed to recover costs.

In Dhaka, prices moved in the opposite direction. Cauliflower that sold for Tk 25 per piece in late December now costs Tk 40–50, depending on size. At Shantinagar kitchen market, cabbage is selling for around Tk 50 per piece.

By contrast, in Sirajganj’s Ullapara upazila, farmer Bhobesh Ghoshal said he sold cabbage at Tk 6–10 per piece in January. “The same cabbages are sold in Dhaka for Tk 20 or more,” he said.

At the Jatrabari wholesale hub, cabbage trades at Tk 25–30 per piece before reaching consumers at Tk 50. For many winter vegetables, the price gap between farmers and consumers ranges from Tk 30 to Tk 40 per unit.

Tomatoes show an even sharper disparity. Early varieties come from Chattogram, while seasonal tomatoes arrive mainly from Rajshahi. In both cases, retail prices in Dhaka have ranged between Tk 100 and Tk 150 per kg.

In Rajshahi’s Godagari upazila, farmer Moktar Hossain said he is currently selling tomatoes at Tk 40 per kg, down from Tk 50–80 earlier in the season. “Middlemen sell those tomatoes in Dhaka at Tk 60 per kg, and prices keep rising along the chain,” he said.

At Dhaka’s wholesale markets, tomatoes sell to retailers at Tk 80–90 per kg and ultimately reach consumers at Tk 100–120. The overall farm-to-table price gap stands at Tk 50–70 per kg.

Radish prices, though lower, follow a similar pattern. In Dhaka, radish sells at Tk 30–40 per kg. In Cumilla’s Gomti char area, farmer Sohrab said radish is sold in bundles.

“One bundle of 8–10 radishes sells for Tk 30, roughly Tk 10 per kg,” he said. “Consumers in Dhaka pay at least Tk 20 more per kg.”

According to a Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) study, more than 700,000 kg of vegetables are sold daily in Dhaka. Even with a conservative price gap of Tk 20 per kg, consumers bear an extra Tk 15 million daily—nearly Tk 500 million over January alone.

Consumers Association of Bangladesh (CAB) President AHM Shafiquzzaman blamed market syndicates and weak oversight. “A group of traders is exploiting the pre-election period to destabilise the vegetable market. Prices have remained high for nearly a month, with no effective monitoring. Extortion at multiple stages of the supply chain is also pushing prices up,” he said.

Warning that prices could rise further during Ramadan, he expressed scepticism about official assurances, calling government data unreliable. He urged authorities to dismantle syndicates, ensure fair prices for farmers, and protect consumers through stricter regulation.

Agricultural economist and former Jahangirnagar University vice-chancellor Abdul Bayes said fair pricing should not rely solely on government intervention. Instead, he emphasised empowering marginal farmers through cooperatives.

“A single farmer from Bogura cannot bring 100 kilograms of cauliflower to Dhaka,” he said. “But if 100 farmers form a cooperative, they can bypass middlemen, secure better prices, and offer vegetables to consumers at lower rates.”

Bayes added that NGOs could support such initiatives and said dismantling syndicates, promoting competition and curbing extortion could help stabilise the vegetable market in the long run.

What's Your Reaction?