Independence was achieved, but true liberation remained elusive

Independence was achieved, but true liberation remained elusive.

The spirit of the Liberation War was, at its core, a dream—a shared dream of collective emancipation. When we speak of this spirit, we distinguish it from the idea of independence. Independence refers to a change in the state’s formal status. By that measure, we achieved independence twice: once in 1947 and again in 1971.

Liberation, however, carries a far deeper meaning. It demands a transformation of the state’s character and a fundamental restructuring of the society within it. Yet despite attaining independence twice, no such foundational change has occurred. The social, political, and administrative structures created during British rule have, by and large, remained intact.

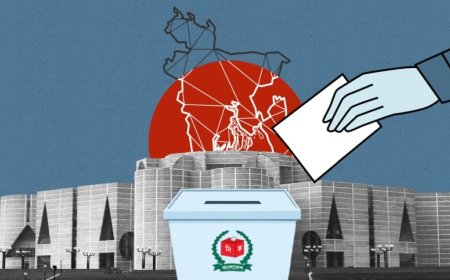

The dream embedded in the Liberation War was precisely this: that society would be transformed, the state would be remade, and political independence alone would not be enough—true liberation would follow. By true liberation, we meant the creation of a humane society and a democratic system of governance. Democracy, at its heart, rests on equality of rights and opportunities. It also requires the decentralisation of power and governance by elected representatives at every level.

In the early stages, this dream of liberation was somewhat indistinct, which is why the struggle initially appeared to be merely a fight for independence. But as mass participation deepened and the collective vision matured, it became clear that this was a struggle for liberation. It was, and remains, a long struggle—one we had not fully understood as such at the time.

Consider the independence of 1947. Then, we spoke only of independence; liberation was not part of the discourse. In reality, there was no genuine struggle for independence in 1947. What took place was communal violence followed by partition—a transfer of power in which the British handed authority to local elites. Power changed hands, but the system remained. It did not take long for the people of East Bengal to realise that true independence had not been achieved and that liberation was still distant. This awareness gave rise to the Language Movement and, through it, the struggle for autonomy.

During the Language Movement, the issue was not language alone. Although Bengalis constituted 56 per cent of Pakistan’s population, the demand for Bangla as a state language was, in essence, a demand for autonomy. This demand continued in successive phases. The 1954 election delivered another verdict in favour of autonomy, and the Six-Point Programme was yet another expression of that aspiration. Gradually, however, the desire for full independence took root among the people. After the victory in the 1970 election, the Six Points condensed into a single demand: the independence of Bangladesh. Only then did the idea of liberation truly begin to crystallise as a collective dream—a vision of a transformed society and state.

The state structure inherited from Pakistan was itself a continuation of British rule: bureaucratic in form and capitalist in economy. We sought to dismantle this structure and establish a genuinely democratic state, but we failed. It is this failure that has condemned us to so much suffering and hardship.

The question, then, is why this happened. We had nurtured a collective dream of liberation—a democratic state and society—but after victory, liberation eluded us. From 16 December onwards, the collective dream that had sustained us through the terror and brutality of 1971 began to fade. During those dark days, despite unimaginable oppression, we held fast to that shared vision. We understood that individual freedom could not exist without collective freedom. Yet after victory, a shift occurred: personal ambitions began to overshadow the collective ideal.

Gradually, the collective dream was set aside as individuals pursued private goals—wealth, power, status, and prestige. Even memoirs of the Liberation War increasingly centred on “my 1971,” “my role,” “’71 and I.” Personal narratives and individual achievements took precedence, pushing into the background the reality that the war was fought through mass participation. New heroes emerged with new stories, and liberation came to be seen as an individual accomplishment rather than a collective one.

As a result, the pursuit of collective liberation was abandoned in favour of personal accumulation. In 1971, we sought freedom together; after 1971, many came to believe that property and wealth would bring freedom—the more one owned, the freer one became. In this way, our golden dream was shattered. What the Pakistani occupying forces failed to destroy, we dismantled ourselves after victory. This was a historic defeat: having won, we abandoned collective thinking and embraced individualism.

Responsibility for this defeat rests primarily with the leadership. Leaders shape ideals, govern the country, and set examples for society to follow. The leadership that led the struggle for independence was nationalist in character, and many of them came to believe that their responsibility ended on 16 December 1971. They did not carry the dream of liberation forward.

The vision of the Liberation War was a humane and democratic society. But those who assumed power after the war were incapable of realising that vision because they were not committed to socialism. They did not seek to advance liberation; they sought only a transfer of power. Just as the British had been replaced by Pakistani rulers, the goal became to replace Pakistani—specifically Punjabi—rulers with ourselves. Through popular struggle, this transfer of power was achieved, but the underlying system remained unchanged. The same laws, the same bureaucracy, the same structures endured.

Those who believe only in a transfer of power cannot be socialists, because socialism demands fundamental transformation of society—ending inequality and establishing equality. That was not the objective of those who came to power. Their aim was simply to take control of the state apparatus, not to remake it.

Yet the true driving force of the Liberation War was the people themselves. They struggled, they suffered, and they sacrificed, but their stories remain largely unrecorded. We lack accounts of their participation, of their hardships, of the violence inflicted upon women. Instead, political parties and the media magnify the roles of a few individuals. As a result, the victory of 16 December did not translate into victory for the collective people.

That is why the struggle for liberation has not ended. It continues—sometimes loudly, sometimes silently—because the dream that inspired the Liberation War remains unfulfilled.

What's Your Reaction?