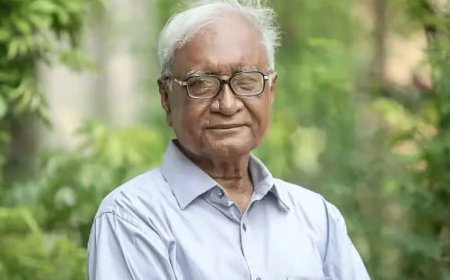

Exclusive Interview: Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed — Real Wages of Workers Declining Annually

The Labour Reform Commission has put forward 25 recommendations aimed at improving workers' rights, including formal recognition of workers, eliminating discrimination, revising wages every three years, and streamlining the trade union registration process. Commission head Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed discussed these proposals as well as pressing concerns such as low wages and the lack of justice for workplace accidents. The interview was conducted by Senior Reporter Shubhongkar Karmakar on 28 April.

Interviewer: In your view, which sector in Bangladesh faces the most worker discrimination?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Discrimination is widespread across all sectors. Take the government secretariat, for example—every ministry employs outsourced workers alongside permanent staff, yet the disparity between the two is striking. During a consultation, a female outsourced computer operator shared how she had to choose between continuing her pregnancy or keeping her job, as she wasn’t entitled to paid maternity leave. She would have had to take two to three months off without pay, whereas permanent employees receive six months of paid leave. In the informal sector, workers have virtually no legal protection. A private driver who has worked for two decades can be dismissed overnight with no remedy. In essence, workers across all sectors face discrimination, income inequality, insecurity, and a lack of protection.

Interviewer: The Commission has recommended wage revision every three years and compensation for delayed payments, among other reforms. These could increase employer costs. Were these proposals accepted unanimously?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Yes, that’s a key strength of the Commission. Despite representing different interests, all members agreed on every recommendation, including financial matters. Employers acknowledged that the current situation is unsustainable—news of workers protesting for unpaid wages is too frequent. They agreed that a disciplined system of wage payments is necessary, including penalties for delays. The Commission firmly believes Bangladesh must move away from its dependence on cheap labour. By building capacity, we can eventually raise wages sustainably.

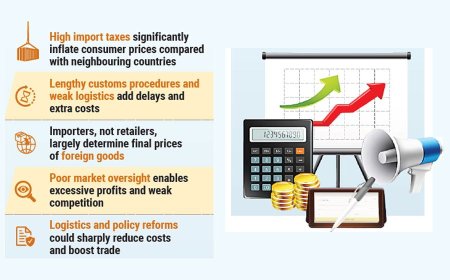

Interviewer: Why are wages in Bangladesh so persistently low?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Part of it is a mindset issue—we tend to treat low wages as a competitive advantage. Secondly, there’s a lack of standardized criteria for determining wages. The Minimum Wage Board sets wages for 42 sectors, but there are no established benchmarks—it often ends in political compromises between employer and worker proposals. That’s why the Commission has proposed a permanent Wage Commission that would conduct research and use data from relevant government agencies to establish fair wage standards.

Interviewer: The Commission has also recommended considering living wage benchmarks in wage-setting.

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Exactly. A living wage is meant to support a decent standard of living—it includes not just basic needs but also savings, children’s education, and dignity. The ILO has clearly defined criteria for this. Many countries follow such models. Just last week, India’s Labour Ministry proposed a minimum wage of ₹27,000—about Tk 35,000. That figure is expected to rise. When a neighboring country takes such steps, we must ask what would be a fair wage in Bangladesh. We need to transition from a model of cheap labour and low-cost products.

Interviewer: Employers in the garment sector often cite challenges when wage revisions come up every five years. Now that the Commission recommends a three-year cycle, what steps are needed for implementation?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Most opposition to wage hikes comes from sectors where revisions are already routine, like garments. But the core issue is this: can employers expect quality work when workers’ real wages are steadily falling? Wages must at least support the reproduction of labour. Real wages have declined year after year, and we no longer have a rationing system—unlike many South Asian countries. If wages don’t keep pace with inflation, revisions are meaningless. Factory owners often blame foreign buyers for low payments, but buyers claim they’re willing to pay fairly. The problem is, that fairness isn’t passed on to the workers. That’s why we’ve proposed a national social dialogue. The Minimum Wage Board also needs to take a more active role and move away from simply balancing employer-worker proposals. Legally, the Board must base wages on family expenses, economic conditions, social needs, and development goals. For instance, if the BBS says a household needs Tk 19,000 per month, that should be the starting point for wage discussions.

Interviewer: Would setting a national minimum wage be the logical first step?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Absolutely. Without a national baseline, wage-setting across sectors can’t be fair or consistent.

Interviewer: Where should implementation begin?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Some steps can be taken right away. For example, our proposed social dialogue forum doesn’t require any legal amendment—it can be established immediately to identify and prioritize issues. Issuing a gazette for a national minimum wage is also straightforward—it just requires data. A digital database to recognize and register workers is another initiative that can begin without delay.

Interviewer: Current compensation for workplace injuries is seen as inadequate. You've recommended increasing it. What standards should guide that?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Compensation definitely needs to increase. There should be a minimum threshold, and in cases of negligence or legal violations, it should be linked to the worker’s income, following ILO Convention 121. We need a formula that reflects varying income levels across the country. After the Rana Plaza collapse, a High Court directive led to the development of such a formula. That framework can guide us now.

Interviewer: Tragedies like Rana Plaza and the Tazreen Fashions fire were never properly prosecuted. What are the implications of this lack of accountability?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: Since Rana Plaza, we’ve seen similar disasters—at Hashem Foods, Tampaco Foils, and a container depot in Chattogram. Fifty children died in the Hashem Foods fire alone. These were preventable tragedies. The root problem is impunity. In areas lacking international oversight, safety rules are ignored. There's no fear of legal consequences for violating labour laws. The prevailing mindset is: even if many die, there may be some outcry and a slightly higher compensation, but there will be no trial. This impunity only deepens the culture of neglect.

Interviewer: The Commission has recommended replacing the percentage-based requirement for trade union registration with a fixed minimum number. What impact would this have?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed: It would bring qualitative improvement. Right now, trade union activity is confined to one or two sectors. We need to expand into the informal sector—construction, day labourers, salon workers, etc. In the current system, when a factory applies to register a union, the labour office first verifies workforce numbers and signatures. This opens the door to corruption, as officials often demand bribes from both sides. Switching to a fixed number rather than a percentage would make the process simpler and fairer.

What's Your Reaction?