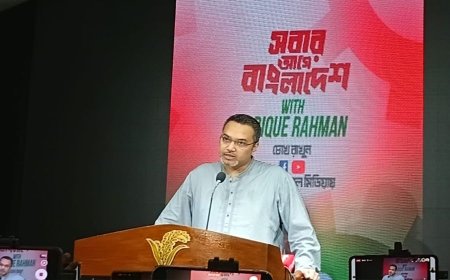

Bangladesh’s Shift from Autocracy to Democracy: Four Key Challenges

Bangladesh’s Shift from Autocracy to Democracy: Four Key Challenges

Bangladesh’s Democratic Transition: Navigating Four Critical Challenges

Bangladesh is currently undergoing a pivotal transition—from a deeply entrenched personalist autocracy to a democratic system. Following nearly 16 years of authoritarian rule, a mass uprising in August 2024 successfully overthrew the regime. The widespread public aspiration now is to establish an accountable, democratic order and ensure that autocracy does not return. Whether the country will succeed in this endeavour is a question with profound implications—not only for Bangladesh’s political future but also for the global discourse on democratisation.

Two Sides of the July Uprising

The uprising in July 2024 was preceded by over a decade of political opposition efforts, but its decisive momentum came from a spontaneous student-led movement. This mobilisation ran counter to the prevailing global trend of democratic decline. According to the Sweden-based V-Dem Institute, the world is currently witnessing a third wave of autocratisation, with 45 countries backsliding into authoritarianism in 2024 alone. In this context, the Bangladeshi people defied global currents, toppling a regime widely considered irreversibly autocratic.

Yet Bangladesh’s experience is not entirely unique. Since the early 2000s, several countries have overthrown autocratic regimes through popular uprisings: Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004), Kyrgyzstan (2005), Nepal (2006), and several Arab Spring nations beginning in 2010—including Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Syria. Beyond the Middle East and North Africa, mass protests also erupted in Thailand (2010), Turkey (2013), and Sri Lanka (2022). The year 2019 alone was dubbed “the year of protest.”

A Historical Perspective

Mass uprisings have deposed authoritarian rulers since at least 1945. Bangladesh itself saw such a movement in 1990. Similar transitions include the Philippines (1986), Indonesia (1998), and Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution (1989). These movements often shared two traits: spontaneity and issue-based mobilisation. Many began with protests over specific grievances—such as price hikes—before evolving into broader pro-democracy movements. Crucially, political parties often joined only later, once public momentum had surged.

The Central Question

How often do such uprisings lead to genuine democracies? According to a 2014 study by Barbara Geddes, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz, only 41% of popular uprisings that ousted autocrats after World War II led to democratisation. This figure likely falls below 40% today. The key question then is: why do so many democratic transitions fail?

Global Lessons: Five Challenges in Democratic Transition

Transitions from authoritarianism are rarely linear. As Jean Lachapelle, Sebastian Hellmeier, and Anna Lührmann note, even successful uprisings only open narrow windows for democratic progress. Based on global experiences, five key challenges repeatedly surface:

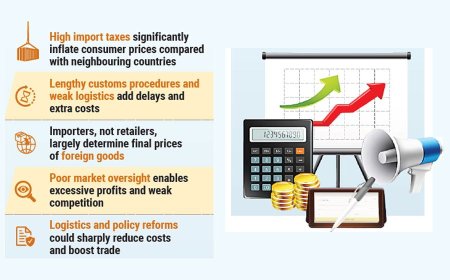

1. Maintaining Stability

The immediate aftermath of an uprising is often marked by chaos and a weakened government. The task of restoring law and order while building legitimacy is difficult—especially when remnants of the old regime resist. Economic disruption typically follows, driven by kleptocratic legacies and capital flight. Former regime allies, often influential in business, withhold cooperation. The result is economic hardship, especially for the middle and lower classes. The Middle East’s post-Arab Spring turmoil, including civil wars, reflects this challenge. Sri Lanka’s recent example offers a more positive contrast.

2. Rebuilding Institutions

Authoritarianism, especially of the personalist kind, hollows out institutions. In transitions, the judiciary and security apparatus become crucial. The experience of Egypt—where civil-military tensions led to a reversal of democratic gains in 2013—shows the risks when militaries resist civilian control. In Sudan, a civilian-military partnership collapsed into renewed conflict. In contrast, Tunisia's military largely stayed out of politics. A successful transition requires firm civilian oversight and genuine institutional independence.

3. Addressing Historical Grievances

Autocracies often leave behind unresolved injustices—ethnic, regional, or political. These grievances cannot be ignored. Truth and reconciliation (T&R) efforts, seen in South Africa and El Salvador, offer mixed results. The process must avoid both exoneration and vengeance. Justice, especially for crimes against humanity, is non-negotiable for democratic legitimacy.

4. Ensuring Inclusive Participation

A critical dilemma is whether and how to include actors from the former regime. Should those complicit in authoritarianism or violence be allowed to participate in the new order? Authoritarian successor parties are common globally. Some adapt and evolve; others resist change. Broad-based, inclusive democracy requires clarity on these questions—and a political culture willing to make difficult compromises.

5. Resisting Autocratic Nostalgia

Democratic transitions often bring instability, which some citizens find disillusioning. A longing for the “order” of the past—a phenomenon dubbed autocratic nostalgia—can undermine new democratic systems. In Tunisia and elsewhere, disinformation campaigns by former regime loyalists have exploited this sentiment. Without clear communication, public engagement, and results, democratic support can erode rapidly.

Bangladesh’s Unique Challenges: Four Strategic Priorities

In the current context, Bangladesh faces four major challenges. These are not simply the responsibility of the interim government; rather, they require collective ownership by the entire political class.

1. Peaceful Transition via Credible Elections

The foundation of any democratic transition is a free, fair, and peaceful election. Examples from Eastern Europe, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka confirm this. In contrast, most MENA countries lacked this crucial step, leading to renewed violence. While the interim government bears the administrative responsibility, political parties must cooperate in good faith—prioritising national transition over short-term gain. The timing of the election must allow for order, fairness, and consensus-building.

2. Reforming the Rules of the Game

The failures of Bangladesh’s institutions over the past five decades show that “business as usual” cannot continue. Constitutional clauses that enabled authoritarian consolidation must be revised. Laws must be restructured, and new accountability mechanisms created. Political parties must commit to reform—not as an abstract promise, but as a new social contract with citizens. This demands introspection, compromise, and a break from clientelist political culture.

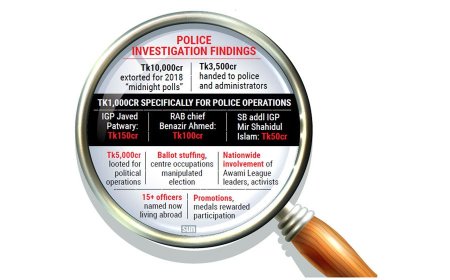

3. Justice for Crimes Committed

Democratisation after repression requires justice. The Sheikh Hasina regime’s post-uprising rhetoric—marked by defiance and threats—mirrors the behaviour of regimes that later collapsed into civil strife. Bangladesh, a signatory to the Rome Statute, must confront crimes against humanity and command responsibility. Justice cannot be delayed or denied without undermining the transition’s moral and legal foundation.

4. Navigating Geopolitical Shifts

Global power dynamics have shifted. A resurgent China, an assertive Russia, and a volatile United States make for a fragile international environment. Bangladesh also faces a regional challenge from India, which openly supported the Hasina regime and shows little sign of policy change. While day-to-day diplomacy lies with the interim government, long-term strategic thinking must come from political parties. A united front and clear vision are needed to protect sovereignty and navigate global tensions.

Conclusion

The July 2024 uprising gave Bangladesh a historic opportunity to establish democratic rule. But success is far from guaranteed. Global experience shows that the journey from uprising to democracy is fraught with dangers—both internal and external. The path forward will depend on how Bangladesh’s political forces engage with the challenges of stability, reform, justice, and strategy. Their choices today will shape the country’s trajectory for decades to come.

What's Your Reaction?