Tug of War Over Elections: Who Sets the People’s Agenda?

Beyond politics, the mass media, intellectuals, rights activists, and civil society have yet to formulate a charter of demands—or even a list of voter expectations and the steps needed to safeguard public welfare.

Elections Without an Agenda: Where Are the People in the Political Tug of War?

As Bangladesh approaches a crucial general election, a fierce tug of war continues over its timing and political conditions. Yet amidst all the noise and negotiations, one fundamental issue remains neglected: what do the people want from this election, and from those who seek to govern them?

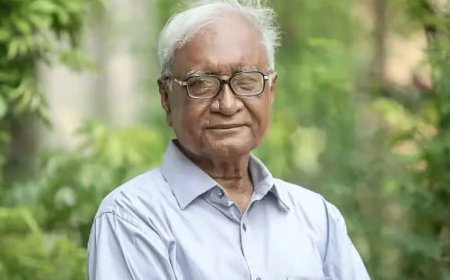

In his 6 June 2025 address to the nation, Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus announced that the next parliamentary elections would be held by the second week of April 2026. Though the announcement quelled some uncertainty, it did little to shift focus toward the most important stakeholder in any election: the ordinary citizen. The political conversation continues to be dominated by power dynamics and elite maneuvering, not by the real hopes and struggles of Bangladesh’s voters.

Even outside formal politics, the situation is no better. The media, intellectuals, civil society actors, and rights groups have yet to come forward with a collective charter of demands—or even a basic outline of what today's voters need or expect. With no structured dialogue about public priorities, and no platforms for citizen engagement, the election risks becoming yet another contest over power, not policy.

Politics as Performance, Not Accountability

In many functioning democracies, election season is a time when political parties actively try to win public trust. They offer solutions to local and national issues, make pledges on development and reform, and try to stand out through debates and outreach. Sometimes they resort to theatrics—accusing rivals, using sharp rhetoric, or appealing to emotion—but the goal remains to engage with voter concerns and secure their confidence.

In Bangladesh, the situation is more complex. The 2026 elections come in the wake of a political awakening—the July–August 2024 uprising, which voiced deep frustration with authoritarian rule, systemic corruption, and broken institutions. Citizens demanded justice, transparency, accountability, and reforms. That movement raised expectations, especially among the youth, for a new kind of politics.

Now, there's a need to carry those aspirations into the electoral process. People want to see that their struggles meant something—that elections will not simply reinstall new faces in the same old system, but deliver real change.

Apathy or Alienation? The Disconnect Between Voters and Candidates

One of the biggest challenges today is the growing disconnection between political candidates and the people they seek to represent. Many aspiring MPs are more focused on securing party nominations and financing expensive campaigns than on listening to their constituents. They may believe that winning votes relies more on party support, personal reputation, or influence than on offering serious policy commitments.

This mindset is reinforced by the structure of Bangladesh’s parliamentary system. In a 300-seat legislature, any party that secures just 151 MPs can form a government. This has led to a dangerous tendency: political parties prioritizing electoral arithmetic over public policy. When power can be won without meaningful promises or public accountability, why bother drafting people-centered manifestos at all?

The result? Elections become an exercise in retaining or seizing power—not in delivering change.

A History of Contrast: From 1991 to 2018

Bangladesh’s electoral history offers both positive and negative lessons. The 1991 elections, held after the mass uprising of 1990, were widely regarded as fair and vibrant. The BNP and the Awami League, then the two largest parties, were compelled to reflect people’s aspirations—shaped by three political alliances’ consensus guidelines—into their campaigns. That public pressure ensured a relatively fair process and a dynamic parliament.

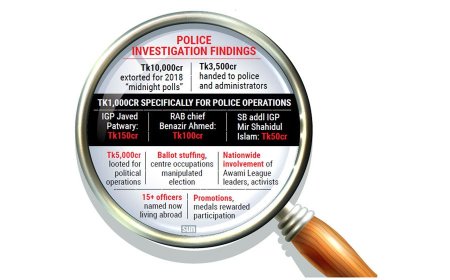

Contrast that with the 2018 elections, where widespread reports of ballot-box stuffing the night before the vote led to massive public disillusionment. The ruling alliance’s campaign music was reportedly more effective at discouraging voter turnout than rallying support. Many voters felt their participation was meaningless—leading to what critics described as a manufactured mandate, not a democratic one.

Real Elections Require Real Agendas

For 2026 to mark a departure from the past, both the interim government and political parties must forge a national consensus on key reform priorities and public interests. This is not merely about reaching across the aisle; it is about reaching out to the people.

Some might argue that parties can still win without engaging in such dialogue. But history—and the uprising of 2024—reminds us that people are the final arbiters. Ignoring their voices can trigger political backlash or destabilize governments. In democracies, public legitimacy cannot be substituted with technical majority.

Prof. Yunus, in his June address, urged citizens to demand firm commitments from political parties and candidates: promises of integrity, an end to corruption and partisan abuse, and genuine adherence to public interest. But such commitments must not remain rhetorical. They need to be part of official party manifestos and election campaigns.

Unfortunately, no institutional mechanism currently exists in Bangladesh for collecting and reflecting public opinion on election agendas. Political parties rarely engage in structured dialogue with citizens, nor do they encourage bottom-up participation in policy formulation. In most cases, the public is treated as a passive audience, not as active agents in shaping their own governance.

The People’s Role: Not Just on Voting Day

Representative democracy—whether in the West or in South Asia—does not mean direct rule by the people. It means choosing those who will govern on their behalf. But for this model to work, public representatives must carry the spirit of democracy—not just its procedures.

This includes:

-

Visiting communities and understanding their concerns.

-

Crafting welfare-oriented policies based on people’s real needs.

-

Respecting the aspirations born out of movements like the 2024 uprising.

-

Seeing elections not as a one-day contest but as part of a long-term relationship with the electorate.

Most voters will never present a written 100-point manifesto. But they carry hopes—of decent jobs, quality healthcare and education, justice, safety, dignity, and a better future for their children. Political parties have a duty to recognize these aspirations and incorporate them into action.

2026: An Opportunity for a New Political Culture

The coming election is not just another vote. It is an opportunity to lay the foundation for a new political culture—one that listens, reforms, and respects the people. As the first anniversary of the 2024 movement approaches, parties and the interim government must seize this chance to connect with citizens meaningfully.

If they fail, the election may once again be reduced to a ritual of power transfer—with little bearing on the lives of those it is supposed to empower.

But if they succeed, Bangladesh could finally begin to fulfill the promise of democracy: government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

What's Your Reaction?