Cautious Budget Fails to Seize Opportunity for Bold Reform

FY2025–26 Budget Proposed at Tk7.90 Lakh Crore

A Budget That Blinked at the Crossroads

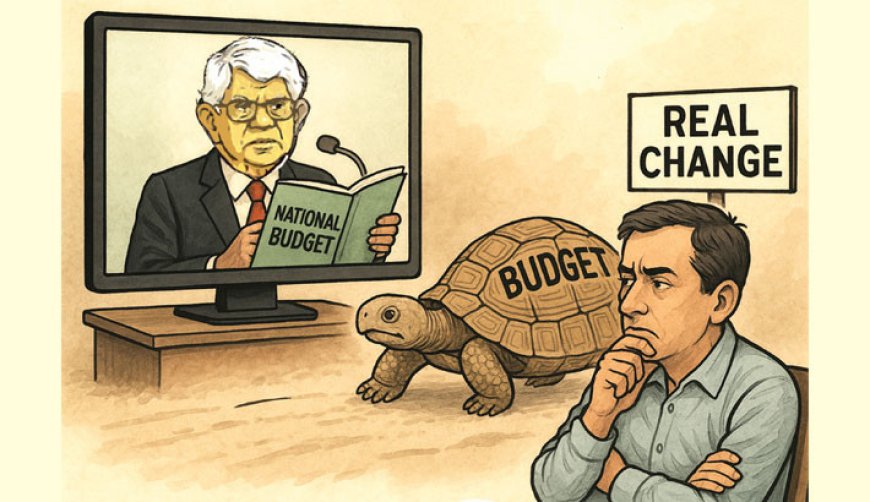

When Finance Adviser Dr Salehuddin Ahmed appeared on screen Monday to unveil the national budget for the 2025–26 fiscal year, expectations were muted but not devoid of hope.

This was the first budget in over 15 years presented outside the framework of a sitting parliament—delivered by a technocratic caretaker administration. In the absence of political baggage and campaign promises, the interim government had a rare chance to introduce bold, long-term reforms. Many anticipated a forward-looking strategy that could reset the tone for Bangladesh’s economic trajectory.

Instead, what emerged was a document that felt overly cautious. It lacked the ambition expected in such a unique moment. More a ledger of numbers than a strategic vision, the budget came across as safe, technical—and underwhelming.

The Budget in Brief

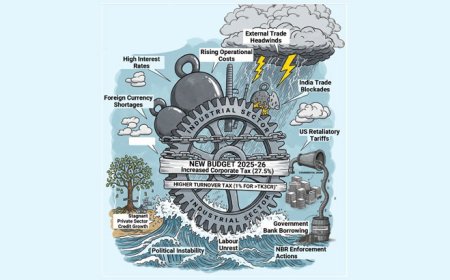

The proposed total budget size for FY2025–26 stands at Tk7.90 lakh crore—down 0.9% from the previous year. This marks the first time in the nation’s history that the national budget has actually contracted. However, this appears to be an intentional move aimed at fiscal discipline rather than an indication of retreat.

Key figures include:

-

GDP Growth Target: 5.5%

-

Inflation Target: Below 8% (from 10.89% in Dec 2024)

-

Revenue Target: Tk5.64 lakh crore (approx. 9% of GDP)

-

Budget Deficit: Tk2.26 lakh crore (4% of GDP)

-

Financing Plan: Tk1.37 lakh crore from domestic banks, Tk98,808 crore from foreign sources

-

ADP Allocation: Tk2.65 lakh crore, prioritising infrastructure, energy, and social services

While the numbers appear technically sound, many observers argue they fall short of inspiring confidence in a country facing economic headwinds and widespread inflationary pressure.

Inflation: The Unmoved Mountain

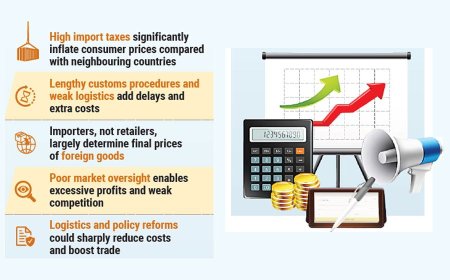

Perhaps the most urgent challenge for Bangladeshis—runaway inflation—received insufficient attention. While the government projects inflation to fall below 8%, for many households, prices remain intolerably high. Essentials like food, rent, and transport continue to strain family budgets.

As Professor AB Mirza Azizul Islam observed, “Inflation here is driven by supply shortages. Tightening monetary policy or hiking interest rates won’t solve that—in fact, it might make things worse.” Raising the policy rate to 10% may please textbook economists, but in a supply-constrained environment, it only deepens pain for businesses and consumers.

Moreover, VAT hikes on daily-use items—from cotton yarn to construction goods—further burden lower- and middle-income groups. While the budget offers exemptions on LNG, milk, and sanitary products, these concessions feel piecemeal compared to the broader price shocks households face.

Dr Mustafa K Mujeri added, “There is no concrete roadmap for how inflation will actually be brought down.” He pointed to inefficiencies in transport, monitoring, and syndicate control of key commodities—issues the budget largely ignores.

Private Investment: Still Grounded

Economic revival is impossible without energising private investment. Yet the budget offers little in the way of structural incentives or regulatory reform to rekindle investor confidence.

Dr Abu Ahmed of Dhaka University summed up the sentiment: “Without investment, there is no growth, no employment, and no poverty reduction. And right now, the private sector faces real barriers—port delays, red tape, infrastructure bottlenecks. The budget doesn’t really tackle those.”

While merchant banks receive a long-overdue tax cut (from 37.5% to 27.5%) and non-listed firms see their rate rise to encourage stock market participation, broader corporate tax reform remains absent. Crucially, SMEs are squeezed further by an extended VAT refund window—from four to six months—an administrative burden they can ill afford.

The e-commerce sector, meanwhile, is hit with a 15% VAT on commissions, adding to the already rising cost of doing business. For many, this budget feels more like a signal to survive than to invest or innovate.

Dr Mujeri warned, “We’re not seeing the kind of robust initiative needed to spark new private or public investment. Without that, employment generation and poverty alleviation will remain stalled.”

Revenue Ambition vs. Ground Reality

The government’s revenue target of Tk5.64 lakh crore—roughly 9% of GDP—is once again described as “ambitious.” But many experts see it as bordering on fantasy.

Dr Zahid Hussain, former World Bank economist, noted: “Even collecting Tk4.5 lakh crore will be difficult. The Tk5.64 lakh crore figure is aspirational without structural change.”

The budget attempts to expand the tax net with symbolic gestures like a minimum tax for low-income earners and digitised collection systems. Yet enforcement weaknesses, distrust in tax authorities, and poor taxpayer services may hinder these goals.

As Professor AB Mirza Azizul Islam cautioned, “Each year, we set high targets, miss them, and then cover the gap by cutting development spending or borrowing more. It’s a dangerous cycle.”

Some Bright Spots—but Not Enough

Despite its shortcomings, the budget isn’t entirely without merit. The healthcare sector benefits from import duty waivers and VAT exemptions on medical goods—a modest but welcome step.

Agriculture receives Tk39,620 crore, along with income tax exemptions up to Tk5 lakh. Increased buffer stock and fertiliser reserves signal some preparedness for climate-related shocks.

The energy sector escapes immediate tariff hikes, and the removal of VAT on LNG imports may stabilise subsidy burdens. Symbolic allocations include Tk100 crore each for youth entrepreneurship and a national youth festival, and Tk200 crore for the blue economy.

However, Dr Mujeri criticised the ADP for padding the budget with “unnecessary mega projects,” which, he argued, lack proper cost-benefit analysis.

The Black Money Dilemma

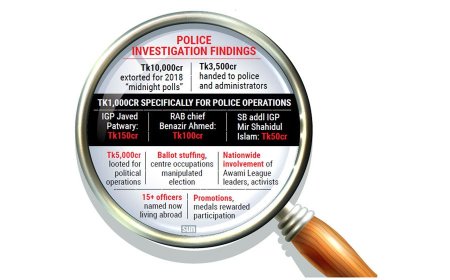

One of the most controversial provisions is the continuation of black money amnesty, especially in real estate. Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB) has condemned it as “unconstitutional, unethical, and discriminatory.”

The move sends the wrong message, especially from a caretaker regime that ought to prioritise integrity. Rewarding undisclosed wealth while honest earners struggle only deepens public cynicism.

A Question of Legitimacy and Timing

At the heart of this budget’s awkwardness lies a fundamental tension: should a non-elected, interim government propose a full-scale budget with sweeping policy changes?

Interim governments are meant to ensure continuity—not to chart transformative paths. In this light, the scope and ambition of the budget feel politically uncomfortable, if not inappropriate.

Dr Abu Ahmed noted, “Political clarity is more important than policy in times like this. Without a credible, inclusive election, no budget—no matter how well-drafted—will restore investor confidence.”

Dr Zahid echoed this sentiment, lamenting the absence of a blueprint to address banking sector vulnerabilities. “Even a minimal signal of policy direction could’ve helped,” he said, “but the budget is silent.”

Conclusion: A Missed Moment

This budget had a unique opportunity to break with business as usual. Instead, it defaulted to the familiar—technical over visionary, safe over bold.

Yes, it includes well-intentioned steps in healthcare, agriculture, and taxation. But inflation remains largely unchecked, private investment lacks stimulus, revenue targets seem unrealistic, and policy on black money undermines its moral stance.

Ultimately, the 2025–26 budget may be remembered not for what it contained—but for what it failed to attempt. In a time of uncertainty, it blinked when Bangladesh needed boldness.

What's Your Reaction?