Exclusive: Mirza Hasan Warns — Without Negotiations, Street Protests Will Resurge

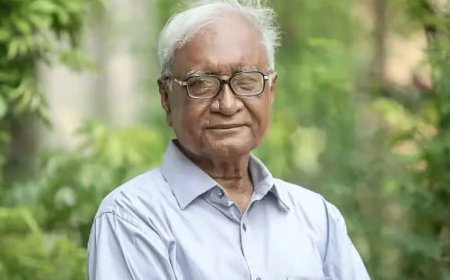

Dr. Mirza Hassan, Senior Research Fellow at the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development, specializes in political research. He holds a Master’s degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a PhD from the University of London. In an interview with Prothom Alo, he discussed topics including reforms, democracy, the role of the interim government, and the present political landscape. The interview was conducted by Monzurul Islam and Khalilullah.

Prothom Alo: It’s been over eight months since the interim government assumed office, with much discussion surrounding reforms. How much progress do you think has been made?

Mirza Hasan: There hasn’t been any significant progress yet. However, several key reform commissions have submitted their reports, so at least now there’s a clear outline of the reforms that are needed. These topics are on the table, and various political parties are engaging in discussions. The Consensus Commission is also holding dialogues with the parties.

The BNP wants to play a decisive role in shaping the reforms, likely because they expect to form the next government. Since many of the proposed reforms seek to place tighter checks on the ruling party, the BNP appears reluctant to fully embrace them. In my view, they are not pursuing any fundamental changes to the old governance system—even though the demand for structural change was at the heart of the recent mass uprising.

Prothom Alo: Some reforms require political consensus, while others could be implemented through administrative orders. Is the interim government taking action on those administrative reforms?

Mirza Hasan: It seems the government believes major reforms should be handled by elected political parties after the elections. Some initiatives have been taken in areas like the economy and banking sector, and steps have been made against corruption and money laundering. However, many reforms that could have been implemented by administrative orders have been left undone, and that’s something that needs to be acknowledged.

Prothom Alo: There’s a perception that the government has fallen into the grip of the bureaucracy. We saw major obstacles from the Home Ministry regarding police reform, for instance. What’s your take on that?

Mirza Hasan: It’s unclear if there's an underlying political agenda, but inter-cadre conflicts are well known, especially regarding police reforms. The administrative cadre's influence clearly affected the Police Reform Commission’s work.

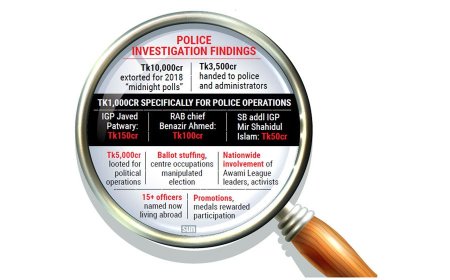

Back in 2007–08, there was a strong push for police reform, but the administrative cadre opposed it then as well. The police have long wanted independence from both political and bureaucratic control. Being used for political purposes has severely damaged the police, which is why they again seek an independent commission.

However, the reform commission recommended further study, which is odd—these experts were appointed precisely for their expertise.

What’s most crucial is transitioning from a "regime police" to a "democratic police," starting with reforms at the local level. Ordinary citizens might not directly encounter authoritarianism from the Prime Minister, but they face it daily from local police officers. Local citizen oversight committees must be created to ensure accountability. Without them, democratic policing will remain elusive.

Prothom Alo: Police and local government reforms aren’t part of the Consensus Commission’s agenda. Does that suggest political consensus isn't needed for these areas?

Mirza Hasan: It appears those leading the commissions view reform mainly as internal reform of political parties and establishing checks and balances within the central government. This is evident in the Constitution and Election Reform Commissions’ recommendations.

Given the immense power concentrated in the Prime Minister’s office, the commissions have proposed measures to limit that power. Their assumption is that if elections, Parliament, and the executive function properly, democracy will follow.

While that’s partly true, democracy is about much more.

Police and local government reforms, along with gender equality, healthcare, education, and labor rights, have been treated as side issues rather than core democratic concerns. This mindset must change if we want real democracy.

Prothom Alo: In your view, what steps are necessary to establish the kind of democracy you're describing?

Mirza Hasan: Citizens must organize themselves—businesspeople, workers, farmers, women, indigenous groups—all need to form representative bodies. These groups should have representation in an upper house of Parliament.

Local citizen councils should also be constitutionally recognized and accountable to national commissions, ensuring checks and balances from the ground up.

Right now, Ward Committees exist but are powerless. Union Council leaders largely ignore them because they lack legal authority. Just as Parliament is captured by ruling parties, so are these local structures. To change that, they must be given a firm legal foundation. Sadly, such topics aren't even part of the current reform discourse.

Prothom Alo: BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami, and the newly formed National Citizen Party (NCP) appear divided on the proposed reforms. Without consensus, is reform still possible?

Mirza Hasan: The public clearly wants change—they reject dictatorship and the politics of self-interest. This desire is reflected in the reform commissions' reports.

I believe all political parties should publicly declare their reform agendas and let voters judge.

Historically, Awami League and BNP have been the main players. Today, the BNP is sidelined, Jamaat is trying to regain footing, and the NCP has emerged. I think the government will seek compromises with smaller parties like NCP and Jamaat.

However, BNP remains their main opponent and may attempt to fragment the other parties. Whether they'll succeed is uncertain.

This is not a caretaker government; it’s a post-uprising government. Many of the reform ideas have come from within it. They say they’ll move forward if there’s consensus, but so far, consensus is missing.

The BNP insists that reforms should be carried out by elected governments, not the interim authority. And they’ve warned they’ll take to the streets if dialogue fails.

We could see a street power struggle between the BNP and the current ruling actors, including the NCP and Jamaat. One silver lining is that the military has expressed a desire to stay neutral, learning from past negative experiences.

Prothom Alo: BNP has repeatedly claimed that the interim government isn't neutral. Meanwhile, NCP convenor Md Nahid Islam recently alleged that the administration favors the BNP. How do you interpret these claims?

Mirza Hasan: Politics naturally involves a lot of rhetoric. Nahid Islam’s comment seems part of that.

It’s true that BNP still holds influence within sections of the government and administration. However, portraying BNP as the new “king’s party” is a political tactic.

Previously, BNP called the NCP the "king’s party." Now, the NCP is trying to flip that narrative, aiming to show that they aren't the government’s favored side.

Prothom Alo: The Awami League faces accusations of trying to establish one-party rule, and several of its leaders are charged with crimes against humanity. Yet, it retains a substantial support base. Should the party be allowed to contest elections?

Mirza Hasan: There’s a lot of contradiction in public discourse.

On one hand, many demand that top Awami League leaders be tried. On the other hand, some argue the party should contest elections.

Personally, I don’t support banning political parties—it’s a political issue that must be resolved politically.

If trials were completed, it would be clearer who is eligible to run.

I don’t think the Awami League can easily separate itself from Sheikh Hasina’s family. If someone else tried to lead it into elections, internal resistance would likely block that move.

Also, opposition parties like the BNP would probably prefer elections without the Awami League present. So, I don’t think it’s time to seriously discuss banning the party.

Prothom Alo: There’s been some talk about the interim government staying in power for five years. What's your view?

Mirza Hasan: When people feel economically stable, they tend to overlook political issues.

Right now, public sentiment seems relatively content. Prices were stable during Ramadan, and Eid travel went smoothly.

Moreover, frustration with both the Awami League and BNP persists.

Against this backdrop, some people casually talk about extending the interim government’s term, but it remains to be seen whether that will gain serious traction.

Prothom Alo: The New York Times recently expressed concern about the rise of extremism in Bangladesh. How do you assess this situation?

Mirza Hasan: The New York Times report isn't entirely wrong, but it does seem somewhat one-sided.

After mass uprisings, the emergence of various new forces is quite normal.

While the government has weaknesses in combating extremism and should be criticised for that, it's unfair to accuse them of actively promoting extremism.

We must also remember how the Indian media has often spread misinformation about Bangladesh. We need to keep these political dynamics in mind when assessing such reports.

Prothom Alo: Finally, what’s your overall assessment of the current political situation?

Mirza Hasan: I’m skeptical about whether a political consensus can be reached.

If dialogue fails, we may see a return to street politics.

Overall, the situation remains highly uncertain.

Prothom Alo: Thank you.

Mirza Hasan: Thank you.

What's Your Reaction?