Can we close the generational divide and revitalize our democracy?

Can we close the generational divide and revitalize our democracy?

Are we witnessing a generational clash between the values and worldviews of Gen Z and pre-millennial generations in our democratic transition? If so, what are the implications as the interim government completes six months in office and begins consultations on reform commission recommendations? How will efforts to build broad consensus on reforms and chart a roadmap for the next phase unfold?

Political parties, despite their differences, are unanimously pushing for early parliamentary elections following "essential reforms" to reclaim government control. The term "essential reforms" appears to acknowledge public demand for institutional and service sector improvements. However, notably absent from their demands are nationwide local government elections that would restore critical services and foster grassroots political engagement. Nor do they advocate for a constituent assembly election to address constitutional and governance structure issues.

What seems to have unsettled the old political establishment is that young student activists succeeded where they had failed. The student-led uprising toppled an authoritarian regime once deemed unshakable, a feat that political parties could not accomplish despite 15 years of struggle. The students’ success was undoubtedly aided by the regime’s extreme brutality in suppressing protests, which galvanized mass support in ways political parties never managed.

As the saying goes, success has many claimants, while failure is an orphan. Political parties argue that their long-term efforts laid the groundwork for the student movement, which merely acted as a catalyst. While there is some truth to this, it does not change the fact that students were the decisive force at a critical moment. Political parties remain reluctant to acknowledge their past failures or accept responsibility for the troubled state of democracy since Bangladesh’s liberation.

Now, the youth are taking the next step, launching outreach campaigns to form a new political party aimed at transforming the entrenched culture of intolerance, polarization, and lack of accountability that has defined Bangladeshi politics. This initiative has triggered mixed reactions from established parties—ranging from cautious acceptance to outright hostility.

Veteran politicians claim to have no issue with a youth-led party, yet their dismissive rhetoric betrays their unease. Their criticisms generally fall into three categories: students should remain students, they lack the experience to govern, and any new youth-led party would merely be a "king’s party" aligned with the interim government. They question whether inexperienced young activists can craft policies or govern effectively. Additionally, the fact that three student movement leaders have joined the interim government fuels accusations that a youth-led party would compromise its neutrality.

The generational divide is evident in public discourse on political transition, the interim government’s performance, and the path ahead. Talk shows and opinion pieces in traditional media—dominated by pre-millennials and millennials—often reflect an implicit generational bias. TV panel discussions tend to feature representatives from existing political parties, media figures, and civil society members, leaving young activists outnumbered. When invited, however, the student leaders articulate their vision clearly, often turning debates into confrontations between generations.

Young activists argue that their movement was not just about holding elections and handing power back to the old parties but about initiating genuine political and institutional reforms to ensure a sustainable democratic transition. Their older counterparts, with minor variations, insist that only an elected "political government" (meaning themselves) should handle reforms. They also criticize the interim government for failing to address immediate economic and security concerns while calling for a quick parliamentary election—though notably not for local government elections.

Mainstream media figures rarely challenge the self-serving narratives of political veterans, and many journalists and commentators appear sympathetic to the establishment’s perspective. While there is broad rhetorical support for youth participation in nation-building, there remains skepticism about their ability to shape the country’s future.

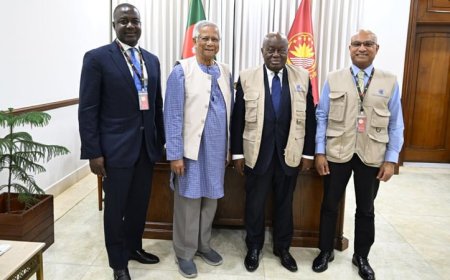

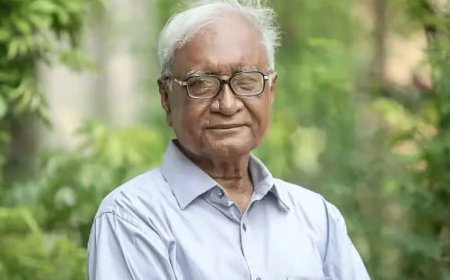

Prof. Muhammad Yunus, however, has consistently championed youth as key drivers of development and democratic progress. He has expressed deep appreciation for the student movement, even calling the students his "employers" for convincing him to lead the interim government. Introducing Mahfuj Alam, a young advisory council member, to former U.S. President Bill Clinton, Yunus described him as the "mastermind" of the movement—an obviously rhetorical statement that nonetheless sparked heated debate in Bangladeshi media. Critics accused Yunus of being excessively deferential to the students, exposing the entrenched resistance to youth leadership.

In a Financial Times interview at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Yunus spoke about young activists mobilizing to form a new party and suggested that such an initiative could help reshape Bangladesh’s political culture. Old-guard politicians immediately pounced, accusing him of favoritism and questioning the interim government’s neutrality. They conveniently ignored ongoing efforts to empower the election commission to conduct elections independently, free from government influence.

Both Gen Z and older generations acknowledge the need for unity in navigating Bangladesh’s democratic transition. There is consensus on the importance of a shared vision and a structured approach to reforms. However, reconciling generationally divergent views on priorities and processes remains a challenge. A pragmatic approach may involve establishing common ground on the "rules of the game"—ensuring fair dialogue and developing a minimum reform agenda that the interim government could initiate and an elected government could carry forward.

As reform commission discussions begin, attention may shift toward defining participation rules for all stakeholders—political parties, civil society, young activists, and anti-discrimination movements—and crafting a foundational reform agenda. One component of this process could be the formulation of a "July Proclamation," symbolizing the ideals of the July-August uprising, with the interim government seemingly eager to contribute to bridging the generational divide.

Holding nationwide local government elections at the union and upazila levels could reengage citizens in the political process and restore essential public services, which have suffered since the dissolution of local councils. Additionally, an agreement to elect a constituent assembly within three months could initiate a democratic process for resolving constitutional and state structure issues with broad public participation. This assembly could draft a new constitution, paving the way for parliamentary elections with redefined structures—such as bicameralism, proportional representation, and improved women's representation—as prescribed in the newly adopted framework.

A phased approach like this would allow the necessary deliberation for far-reaching democratic reforms, ensuring that the generational divide is addressed in a constructive, inclusive manner.

What's Your Reaction?